Words Eloise Hallo

Tim Burton’s Edward Scissorhands may not strike the reader as a cookie-cutter Christmas classic. Yet, its narrative, which loosely follows the idea of small-town suburbia – set amidst, in part, the backdrop of the festive holiday period – situates its spot, as far as I’m concerned, on the yearly December watchlist. Beyond the obviousness of snow and gaudy coloured bulbs, which permeate the latter end of the film, its story of an outlier who finds love is not dissimilar in sentimentality to other festive classics we all jointly watch and re-watch in commemoration of the year’s term. Its ultimate tragedy, however, in that Edward may not keep the love he finds, is a testament to his Burtonian creator, who asks us to reconsider the conventions we have surrounding a nucleated Christmas and how such festivities may feel to those either literally or self-perceivably on the outskirts. Characteristically, Edward (played by a young Johnny Depp), as outlier and reject, figure-headed the growing mentality in youth culture of disenfranchisement from and disinterest in the idea of being an ‘upstanding member of society’. What had, for their parents, meant working a 9–5 and settling down with someone of a similar upstand-ment. Stylistically (thanks to costume designer Colleen Atwood), he represents what this move was to be termed and, when having found its fashioned feet, adorned in; grunge.

Just as important as Atwood’s conceptions of grunge in the film, which are in part pre-conceptions of the aesthetics posthumous reckoning, are her portrayals of normalcy. It is, unsurprisingly, essential that, for Edward to be seen as different, Atwood and Burton must conjure a consistent account for what it means to be the same, an effect which is largely created through their fashion choices. From its beginning, a hyper-saturated 60’s styling is set as the unnamed town’s norm. A notion true also of the town itself, what production designers quite conveniently imagined as ‘if Leningrad had an American type housing complex’.

At risk of becoming too tantalisingly preoccupied with how exactly a town like that may have functioned, being that this article is about fashion, I’ll move myself quickly onto the message Burton and his designers set: simply, that convention, in whatever respect we take it, is always and dangerously conducive to a lack of individuality. And, despite the vast and seemingly exciting colouring to the townspeople’s wardrobes’, certain stills play right into this hand, as in the juxtaposition of mise-en-scene in the two below.

Though the appearance of Edward’s unassuming co-ord would suggest it is he who lacks substance, the vapid nature of conversation in both scenes farcifies their outfitting by opposition. The simple fact that he is othered by his lack of colour and unsaturated by an attempt to feign intrigue positions him as different, and for that difference, better: an unwitting renegade of a small-town hive mind. Edward’s othering is, however, not solely a product of the work’s styling in a literal sense. Our protagonist, both consciously and otherwise, ostracises himself from normality and nucleation, as in the saddening scene he hedges the family and is not included.

In this respect, Edward’s fashioning takes on a more abstract vein, becoming reminiscent of the self-professed outcast who does not feel they fit into typical society; an archetype largely popularised and newly celebrated in the decade to which the film belongs. Edward’s self-perception, which forms an outcry of the angsty teen-hood to director Burton himself, is a precursor to the same sensibility that would see teenagers trade Wham! for Nirvana and nauseatingly neon boiler suits for near enough entirely black dress.

More expansively, Johnny Depp’s character symbolises the true and well-known notion that there is genuineness to those individuals committed to being unreservedly oneself, and the irony that Edward is in fact artificial – and quite literally man-made – works to emphasise the ideal that it is he who stands strong-in-self against the back lay of manufactured identities within whom he will meet contempt upon arrival and acclimation to the town. Simply, Edward – the lovable weirdo with the unfortunate vice of weaponry for hands – in his famous phrase, ‘we are not sheep’, acted as a billowing call to arms for young square-eyed teens of the 90s that they need not be sheep either; a sentiment glowingly encapsulative of the grunge groundburst that was to soon enwrap the world.

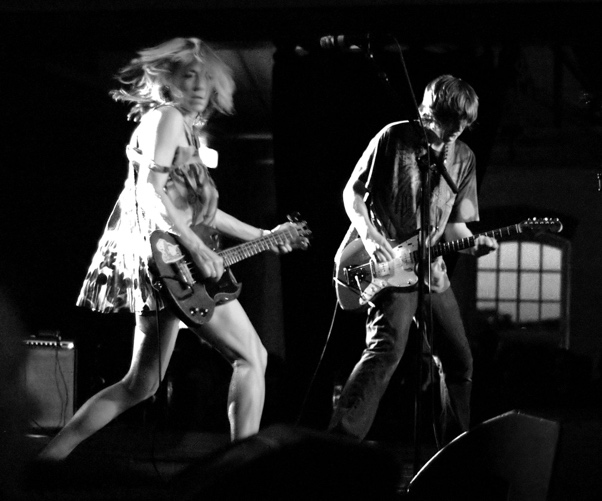

(Sonic Youth, Stockholm, 2005.)

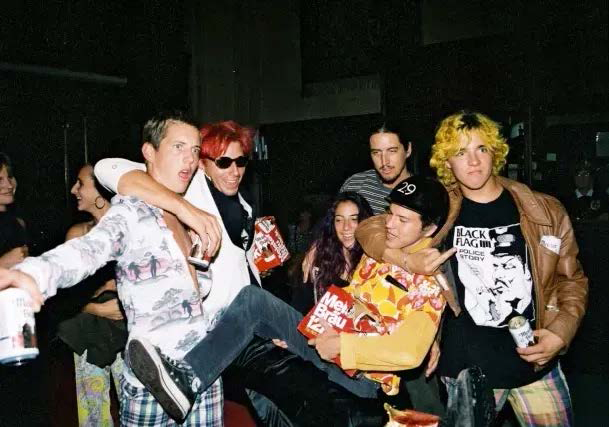

(Eddie Vedder of Pearl Jam, and friends, 1992.)

And enwrap it truly would. Bourne as a melange of 80’s metal and post-punk alt-rock, the culture was to be firmly grounded in music, these beginnings – as is so often true – giving way to middles and ends heavily concerned with, and by, fashion. Its overarching theme was to be the disenfranchisement of youth, and, stylistically and musically alike, the adornments of the counter-culture were bleak wrestlings with attempts to find meaning in a hyper-saturated and commercialised society, from which so many young people felt disparaged. Because of this, such adornments were heartily reactionary from the materialism that the aesthetic came to resent. Note: A not dissimilar kind of resentment belies Burton’s portrayal of materialism through the townspeople in Edward Scissorhands. The culture’s fashioning was characterised by dark colours and ill-fitting second-hand clothes, all of which intended to externalise the sentiment of not wanting, in fact quite actively discouraging, being looked at or spoken to. And so, for the teens of grunge’s new-age, Edward would sit as a paragon, both affirming and ‘protagon-ising’ this very feeling of loneliness, which had, otherwise – and in other films – been used to depict characters as strange maliciously, rather than peculiar, and, for those peculiarities, remarkable.

All the more heart-warming is it that Edward does not remain alone in his unorthodox. Kim, played by Winona Ryder, is so moved by Edward’s enduring endearment that her characterising, which starts as popular cheerleader – and is styled in tones resemblant to the rest of the town – shifts, in the film’s final acts, to the neutral tones connotative of non-convention in the Edward Scissorhands-verse, in which she newly and solely joins her love interest, our protagonist, who has been without a companion nearly his whole life.

Burton’s conceptions of outlier-hood, which would prove seminal to the humming grunge movement, found their way into the haute spotlight not long after. Marc Jacobs’ infamous show for Perry Ellis in 1992, ‘Grunge Collection’, was an ode to the Seattle-based scene. Models, like Naomi Campbell, Kate Moss, and Chrissy Turlington, sporting Doc Martens, flannel, and – if you can believe it – beanies, proved a thing so controversial that renowned fashion critic Cathy Horyn would deem the show, and the counter-culture it championed, an ‘anathema to fashion’, a sentiment she would later retract in a 2018 article by The Cut, ‘it’s hard to believe we were so offended’, she coyly acquiesces. Regardless, Jacobs would be near immediately fired from his house in a quite perfect dramatisation of misfit culture, willing individuality, and being ostracised for the both.

Edward Scissorhands is not often thought of as a foreperson to grunge culture, nor is its narrative widely considered to be a festive feel-good. Yet, the story of a broody outcast who is, at least in part, allowed to play house and try his hand at an unconventionally beautiful, albeit doomed, love wonders on the strength of both claims. For me, Edward Scissorhands narrates the particular toil of feeling misunderstood; something entirely nonspecific to the culture of grunge, and, in fact, quite akin to the inner child, or angsty teen, many of us are returned to in the holiday period. Nonetheless, Burton reminds us it’s okay to wear black at Christmas, and, while everyone fights over the turkey or gravy, it’s alright to sit in the corner and listen to Deftones.

Sources

Opening image

https://i.pinimg.com/originals/6d/96/40/6d9640119337150038b25ed7478fcdb2.jpg

Stills otherwise from Edward Scissorhands dir by. Tim Burton (1990), 20th Century Fox., Amazon Prime, [accessed] https://www.amazon.co.uk/Edward-Scissorhands-Dianne-Wiest/dp/B00FYHVBE8/ref=sr_1_1?crid=CPMUBYM4USMJ&keywords=edward+scissorhands+movie&qid=1702394315&s=instant-video&sprefix=edward+s%2Cinstant-video%2C67&sr=1–1

‘Sonic Youth, 2005’.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:SonicYouth.JPG

‘Eddie Vedder, 1992’.

https://theculturetrip.com/north-america/usa/washington/articles/a‑brief-history-of-grunge-the-seattle-sound

Cathy Horyn in ‘The Cut’

https://www.thecut.com/2018/11/marc-jacobs-1992-grunge-collection-reissue.html

‘Edward and Kim’

https://www.pinterest.co.uk/pin/702420873146120615/